A few months ago, Svelte 3 was released.

I tried it out, ran through their tutorial, and built a few small things. And I can honestly say that I think writing Svelte feels even faster and easier than React. Svelte gave me the same spark, the same feeling of “wow!” that I had with React.

In this post I want to tell you a bit about Svelte, show you how it works with a few live example apps, and point you toward how to get started.

What is Svelte?

Svelte (some might say SvelteJS, but officially just “Svelte”), currently in its third revision, is a front end framework in the same vein as React, Vue.js, or Angular. It’s similar in that it helps you paint pixels on a web page. It’s different in a lot of other ways.

Svelte is Fast

One of the first things I noticed about Svelte was how fast it is.

The execution time is fast because Svelte surgically updates only the parts of the DOM that change. In contrast to React, Vue.js, and other Virtual DOM frameworks, Svelte doesn’t use a virtual DOM.

While VDOM frameworks are spending time rendering your components into an invisible tree before they commit changes to the real DOM, Svelte skips that middle step and goes straight for the update. Even though updating the DOM might be slow, Svelte can do it quickly because it knows exactly which elements changed (more on how that works in a minute).

Svelte is also fast to develop in. In general, it seems like Svelte components tend to have less code than the equivalent React component. We’ll see more examples in a bit, but here’s Hello World in Svelte, for reference:

<script>

let name = "World"

</script>

<h1>Hello {name}!</h1>That’s it! That’s a Hello component. The variable name is declared in a regular old script tag. Then that variable can be used within the HTML below. It’s almost just an HTML file.

Here’s a React Hello component for comparison:

import React from 'react';

const Hello = () => {

let name = "World"

return <h1>Hello {name}!</h1>;

}

export default Hello;Still pretty short, but with more special syntax to understand.

Svelte is Small

When a Svelte app is compiled, the resulting bundle size is tiny compared to most other popular frameworks.

Here’s that Hello World app, running on this very page:

The bundle.js file for that app is 2.3KB. And that includes Svelte! One JS file.

That’s smaller than the tiny + awesome Preact React-compatible library, which starts at 3kb for just the library on its own. And the Hello React example above came out as 124KB of JS files after a build with Create React App.

Okay, okay, that’s not gzipped. Let me try that real quick…

$ gzip -c hello-svelte/public/bundle.js | wc -c

1190

$ gzip -c hello-react/build/static/js/*.js | wc -c

38496That works out to 1.16KB vs. 37.6KB. After it’s unzipped, the browser still has to parse the full 2.3KB vs. 124KB though. Tiny bundles are a big advantage for mobile.

Another nice thing: the node_modules folder for this Hello World Svelte app totals only 29MB and 242 packages. Compare that to 204MB and 1017 packages for a fresh Create React App project.

“Yeah whatever Dave, those numbers don’t matter. That’s a contrived example.”

Well, yes. Yes it is! Of course a large, real-world app will dwarf the size of the framework that powers it, whether that’s 1k or 38k. That’s the baseline though, and personally, I think starting with such at tiny+fast footprint is exciting.

And even for larger apps, I think Svelte might have an ace up its sleeve because…

Svelte is Compiled

The reason Svelte apps are so tiny is because Svelte, in addition to being a framework, is also a compiler.

You’re probably familiar with the process of running yarn build to compile a React project. It invokes Weback + Babel to bundle up your project files, minify them, add the react and react-dom libraries to the bundle, minify those, and produce a single output file (or maybe a few partial chunks).

Svelte, by contrast, compiles your components so they can sorta run on their own. Instead of the result being (your app) + (the Svelte runtime), the result is (your app that Svelte has taught how to run independently). Svelte bakes itself in, taking advantage of tree shaking from Rollup (or Webpack) to include only the parts of the framework that are used by your code.

The compiled app does still have some Svelte code in there, like the bits it adds to drive your components. It doesn’t magically disappear entirely. But it’s inverted from the way most other frameworks work. Most frameworks need to be present to actually start and run the app.

Build a Shopping List in Svelte

Ok ok, enough talking about how fast/small/cool Svelte is. Let’s try building something and see what the code looks like.

We’re gonna build this shopping list right there:

We’ll be able to add things to the list, remove the mistakes, and check them off as you buy them.

Here’s our starting point, a hardcoded list of items to buy:

<script>

let items = [

{ id: 1, name: "Milk", done: false },

{ id: 2, name: "Bread", done: true },

{ id: 3, name: "Eggs", done: false }

];

</script>

<div>

<h1>Things to Buy</h1>

<ul>

{#each items as item}

<li>{item.name}</li>

{/each}

</ul>

</div>At the top, there’s a <script> tag, and at the bottom, some HTML markup. Every Svelte component can have a <script>, a <style>, and some markup.

Within the <script> is regular JavaScript. Here we’re defining an array called items, and that variable becomes available in the markup below.

In the markup, you probably notice most of it looks like normal HTML, except this part:

{#each items as item}

<li>{item.name}</li>

{/each}This is Svelte’s template syntax for rendering a list. For #each of the elements in the items array (call it item), render an <li> tag with the item’s name in it.

If you know React, the {item.name} will look familiar: it’s a JavaScript expression within the template, and it works the same as it does in React. Svelte will evaluate the expression and insert the value into the <li>.

Remove Items From the List

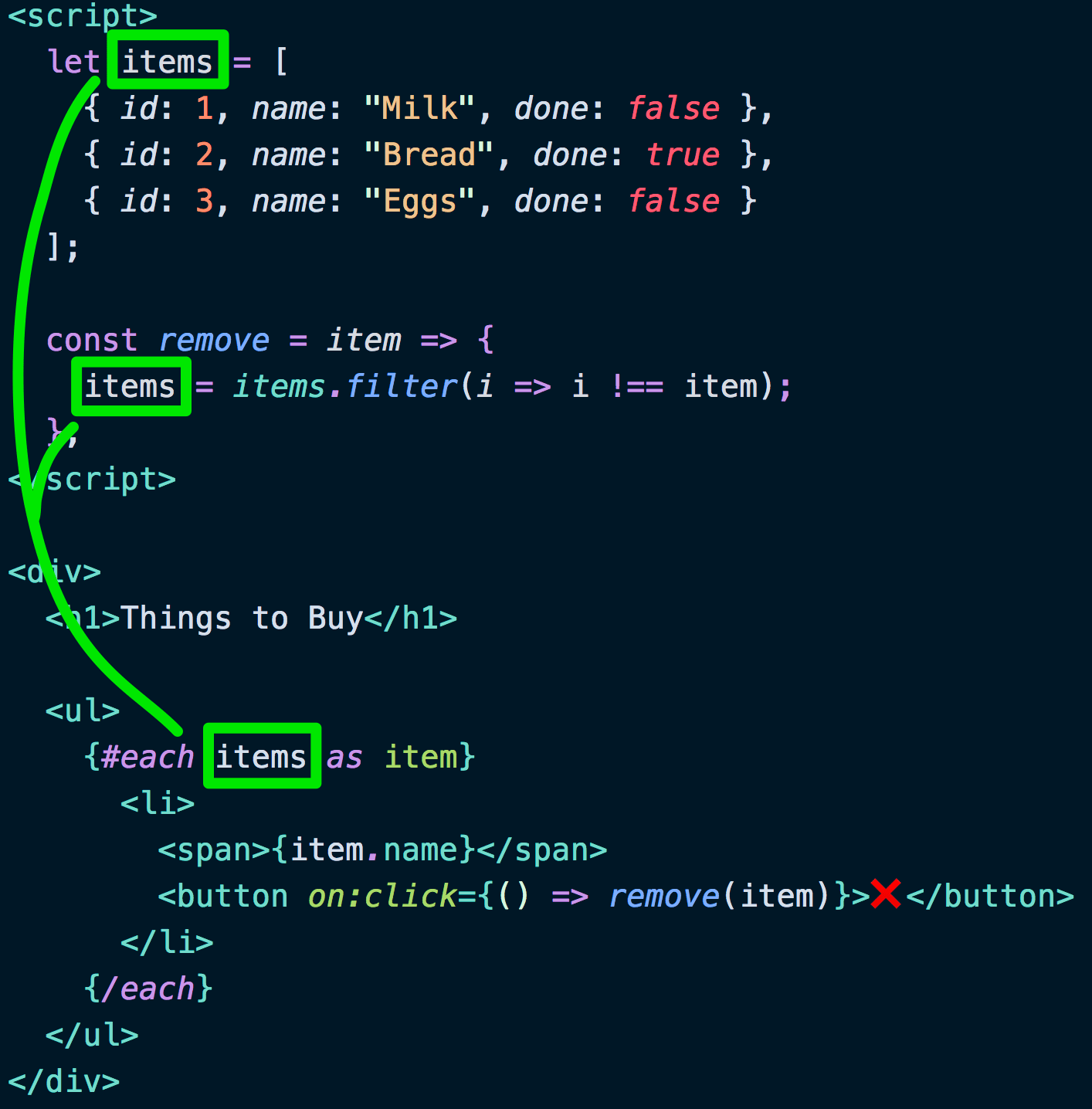

Let’s add another feature: removing items from the list. Here’s the new code:

<script>

let items = [

{ id: 1, name: "Milk", done: false },

{ id: 2, name: "Bread", done: true },

{ id: 3, name: "Eggs", done: false }

];

const remove = item => {

items = items.filter(i => i !== item);

};

</script>

<!-- ooh look, a style tag -->

<style>

li button {

border: none;

background: transparent;

padding: 0;

margin: 0;

}

.done span {

opacity: 0.4;

}

</style>

<div>

<h1>Things to Buy</h1>

<ul>

{#each items as item}

<li>

<span>{item.name}</span>

<button on:click={() => remove(item)}>❌</button>

</li>

{/each}

</ul>

</div>We’ve added a couple things here.

First, we have a remove function inside our script now. It takes an item, filters the item out of the array, and, crucially, it reassigns the variable items.

const remove = item => {

items = items.filter(i => i !== item);

};Svelte is Reactive

When you reassign a variable, Svelte will re-render the parts of the template that use it.

In the example above, the resassignment of items is what causes Svelte to re-render the list. If we had just pushed the item onto the list (items.push(newThing)), that wouldn’t have had the same effect. It’s gotta be items = something for Svelte to recompute. (it also notices assignments to properties, like items[0] = thing or items.foo = 7)

Svelte is a compiler, remember. That makes it able to inspect the relationships between the script and the template at compile time, and insert little bits of code that say “Re-render everything related to items now.” In fact, here’s the actual compiled version of the remove function:

const remove = item => {

$$invalidate('items', items = items.filter(i => i !== item));

};You can see the resemblance to our original code, and how it’s been wrapped with this $$invalidate function that tells Svelte to update. It’s nice how readable the compiled code is.

Event Handlers Start With ‘on:’

We also added this button with a click handler:

<button on:click={() => remove(item)}>

❌

</button>Passing a function this way will look familiar if you’re used to React, but the event handler syntax is a little different.

All of Svelte’s event handlers start with on: – on:click, on:mousemove, on:dblclick, and so on. Svelte uses the standard all-lowercase DOM event names.

Svelte Compiles CSS, Too

The other thing we added to the code above was the <style> tag. Inside there you can write regular, plain old CSS.

There’s a twist, though: Svelte will compile the CSS with unique classnames that are scoped to this specific component. That means you can safely use generic selectors like li or div or li button without worrying that they will bleed out into the entire app and wreak havoc on your CSS specificity.

- here’s a list

- on the same page as the Grocery List app up there

- and the styles don’t conflict!

Speaking of CSS, we need to fix something.

Dynamic Classes with Svelte

You might’ve noticed a bug in our app: one of the items is marked as “done”, yet it doesn’t appear that way in the list. Let’s apply the CSS class done to the completed items.

Here’s one way to do it… if you’re familar with React, this will look pretty normal:

{#each items as item}

<li class={item.done ? 'done' : ''}>

<span>{item.name}</span>

<button on:click={() => remove(item)}>❌</button>

</li>

{/each}Svelte uses regular old class for CSS classes (unlike React’s className). Here we’re writing a JS expression inside curly braces to compute the CSS class.

There’s a nicer way to do the same thing, though. Check this out:

{#each items as item}

<li class:done={item.done}>

<span>{item.name}</span>

<button on:click={() => remove(item)}>❌</button>

</li>

{/each}This bit, class:done={item.done}, is saying “apply the class done if item.done is truthy”.

Svelte has a lot of these little niceities. They know we developers do this kind of thing all the time, so they added a shorthand for it. But it’s also nice to be able to revert to the “hard” way if you need to do something special, or if you just forget the shorthand syntax.

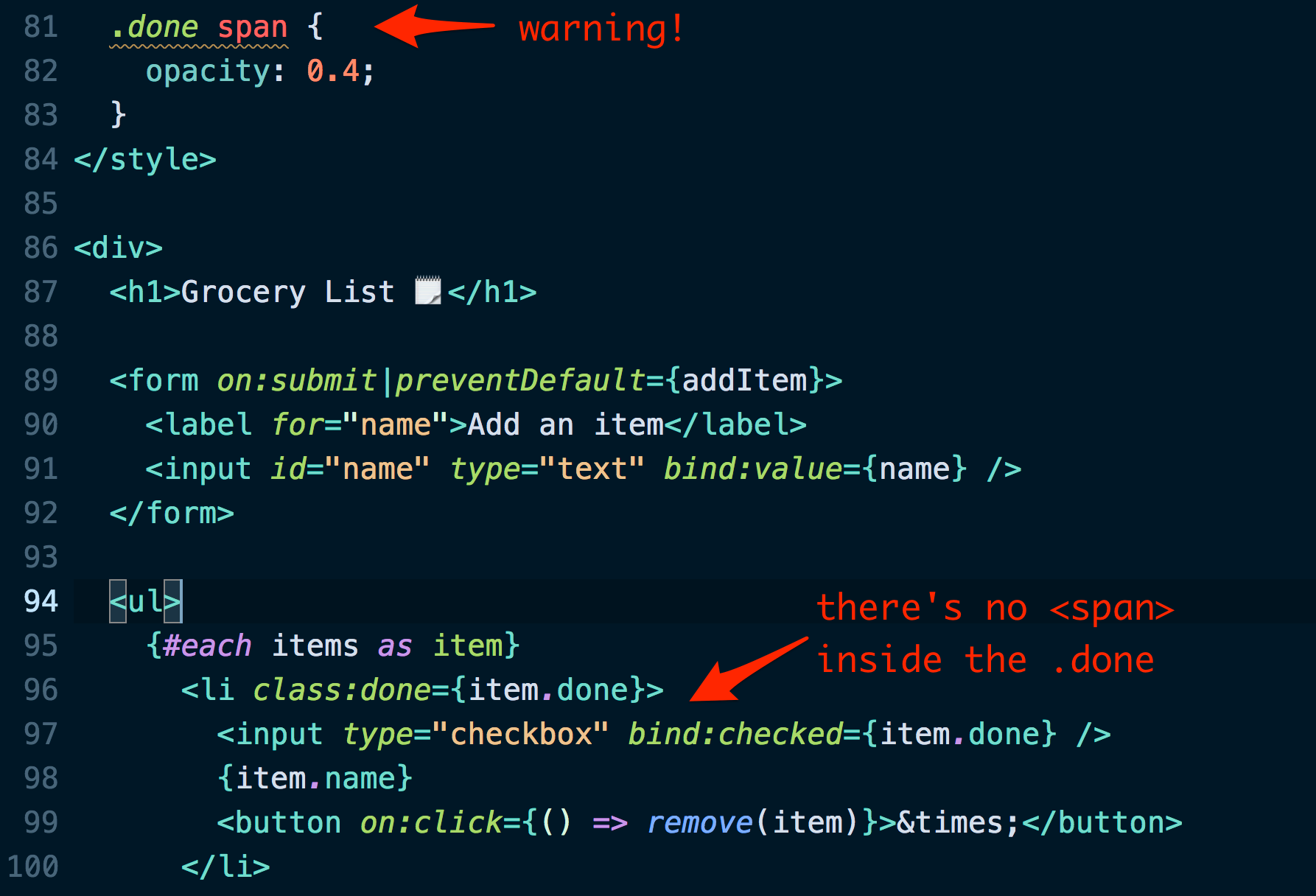

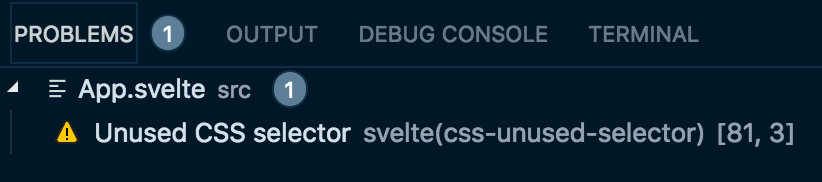

Svelte Detects Unused CSS

A nice side effect of Svelte compiling the CSS is that it can determine if some of your CSS selectors are unused. In VSCode, it shows up as a yellow squiggly line right on the rule itself.

In fact, as I was writing the code for this blog post, it helped me catch a bug. I wanted to dim the {item.name} when it was marked as “done”, and to do that I was gonna wrap it in a span. I forgot to add the tag, though, and wrote the CSS selector .done span to target the non-existent span. This is what I saw in the editor:

And the same warning appeared in the Problems tab:

It’s nice to have the compiler watch out for like that. Unused CSS always seemed like a problem computers should be able to solve.

Mark Items as Done

Let’s add the ability to toggle an item’s “done” status on or off. We’ll add a checkbox.

One way to do it is to write a change handler to synchronize the value as we’d do in React:

<input

type="checkbox"

on:change={e => (item.done = e.target.checked)}

checked={item.done} />A more Svelte way to write it is to use bind:

<input type="checkbox" bind:checked={item.done} />As you check and uncheck the box, the bind:checked will keep the checkbox in sync with the value of item.done. This is two-way binding and it’ll look familiar if you’ve used frameworks like Angular or Vue.

Forms and Inputs and preventDefault

The one big thing still missing is the ability to add items to the list.

We will need an input, a form around it (so that we can press Enter to add items), and a submit handler to add the item to the list. Here are the relevant new parts:

<script>

// ... existing stuff here ...

// new stuff:

let name = "";

const addItem = () => {

items = [

...items,

{ id: Math.random(), name, done: false }

];

name = "";

};

</script>

<form on:submit|preventDefault={addItem}>

<label for="name">Add an item</label>

<input id="name" type="text" bind:value={name} />

</form>We’ve got the addItem function to, well, add the new item to the list. Notice that it reassigns items instead of doing an items.push(), and then resets the name. Those changes will cause Svelte to update the relevant bits of UI.

We haven’t run across on:submit and bind:value yet, but they follow the same patterns we saw earlier. The on:submit calls the addItem function when you submit the form, and bind:value={name} keeps the string name in sync with the input.

Another interesting bit of syntax is the on:submit|preventDefault. Svelte calls that an event modifier and it’s just a nice shorthand to save us having to call event.preventDefault() inside our addItem function – though we could just as easily write it that way, too:

<script>

const addItem = (event) => {

event.preventDefault();

// ... same stuff here ...

};

</script>

<form on:submit={addItem}>

<!-- same stuff here -->

</form>And with that, we’ve finished the app. Here it is again so you can play around with it:

Where to Learn More

There’s a ton more awesome stuff in Svelte that I didn’t have space to cover here, like:

- creating more than one component…

- passing props to components

- slots (they work like React’s

children) - reactive statements to do things like “recompute

namewhenfirstNameorlastNamechange” or “print thefirstNameto the console when it changes” - the

{#await somePromise}template block - animations and transitions built in

- lifecycle methods like

onMountandonDestroy - a Context API for passing data between components

- Reactive “stores” for global data

The official Svelte tutorial covers all of this and more, and the tutorial is great, with an interactive “lesson” for each concept. Definitely check that out.

The Svelte site has a nice REPL for playing around in the browser. Here is the grocery list example that we’ve built, or you can start a new app at svelte.dev/repl.

It’s still early days for Svelte, but I’m excited to see where it goes.

One more thing! The creator of Svelte, Rich Harris, gave an excellent talk called Rethinking Reactivity about the motivations behind Svelte and also a bunch of cool demos. Definitely check that out if you haven’t seen it. Embedded here for your viewing pleasure: