Block scope with let and const

In the JavaScript of yesteryear (ES5), you’re used to writing var at lot. And mostly it works the way you expect it to.

But you can run into strange bugs if you forget (or never knew) that var doesn’t create block-scoped variables the way other languages do.

See, var is scoped to its containing function (or global), not its containing block. This is big difference if you’re used to… well, almost any other language.

let solves this problem.

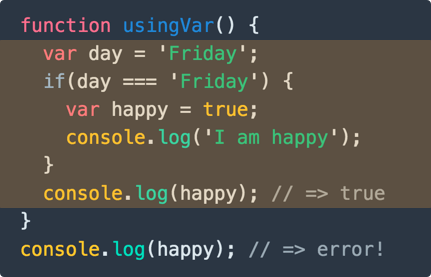

Here’s a quick refresher on how var’s function scope works:

The variable happy is available everywhere in the highlighted area – notably, it is still in scope after (and before) the block it’s declared in.

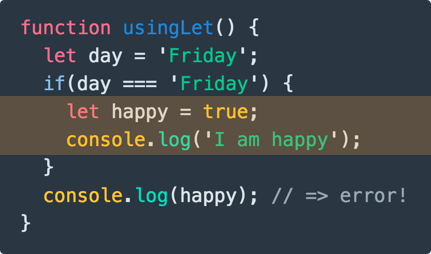

Now, here’s the same example using let, which has block scope:

See how the highlighted area is confined to that single if block? This will be familiar to those coming from other languages where block scope is the norm. Block scope helps avoid subtle bugs.

for loops

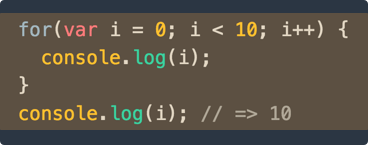

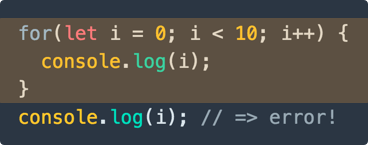

Using let to declare the index in a for loop now works “as expected” (if you’re familiar with C/C++/Java/C#/…):

Here’s var, where declaring that variable at the top of the for loop actually leaves it in scope after the loop is done:

Now here’s let, doing the sensible thing, confining the variable to the loop because of block scope:

Closures in loops

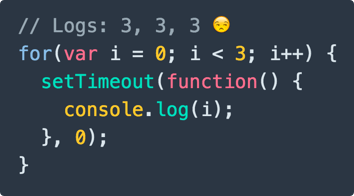

Here’s a weird side effect of using var inside a closure that’s created inside of a loop. This could happen if you, say, want to set up a bunch of timers:

It prints “3”, 3 times… instead of the expected “0, 1, 2”. WAT? What’s going on?

Closures capture the values from the current scope. But not like a snapshot in time… more like a reference to a variable name. Since the scope is the same each time a closure is created, all 3 closures reference the same variable.

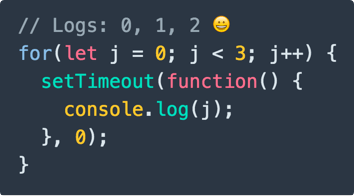

Using let fixes this:

const

Alright, let’s talk about const (see what I did there?).

const is block-scoped, just like let. The only difference is that it can’t be reassigned or redeclared.

const myName = "Dave";

// No reassignment:

myName = "Joe"; // nope

// No redeclaration:

const myName = "Joe"; // nope

var myName = "Joe"; // nope

let myName = "Joe"; // nopeYou also must give it a value at declaration time. const variables can’t sit around unassigned. No “first assignment wins” here.

const iWillDecideLater; // nope

const iWillDecideNow = true; // ok.Notice I said things declared as const can’t be reassigned.

I didn’t say they couldn’t be changed… the value of a const is not immutable.

const someObject = {name: "Dave"};

someObject = {name: "Joe"}; // error: can't reassign

someObject.name = "Joe"; // this is allowed though!This only applies to Objects, Arrays, and Functions, though – they’re the only mutable types in JS. If you declare a const Number, String, Boolean, Null, Undefined, or Symbol (new to ES6), those are primitive types and they will in fact be immutable.

For the C/C++ folks: ES6 const is like a constant pointer to an object rather than a pointer to a constant object.